I Had A Raspberry, Don't Tell God

How to Break-Up Ethically

How fitting that the first day of October was the first crisp fall day in New York City. After a long and drawn-out summer of humidity, we were all more than happy to unpack our sweaters and boots and feel the cold wind against our faces. How fitting, as well, that the first fall day fell upon the night of Yom Kippur.

Yom Kippur is the night when we Jews atone for our sins by fasting from food and water until Sundown the next day. Like many religious traditions, we carry it out without ever really thinking about why. We all sin, and we all have much to ask forgiveness for, but it does strike me as odd that those of us who masturbate fast for the same amount of time as mass murderers. Shouldn’t there be tax brackets or something?

The Jewish God is angry. He treats his subjects (who are allegedly made in his image) like a Republican dad after his son brought home a boyfriend to Easter brunch. With all his floods, plagues, and time-outs, it’s no wonder devout religious types refer to themselves as “god fearing.”

Every year around this time, I reflect on where I’ve fallen short of the standards I hold myself to, and how I can improve. This year, I have been trying to atone with God for the fact that I broke up with my girlfriend poorly. More than that, I don’t feel terribly bad about breaking up with her, which makes me feel even worse because I think I’d feel better if I felt worse.

We dated for a year and a half, which is nothing to shake a stick at. That’s almost two pregnancies! It was a wonderful relationship, and I will hold the memories fondly. But yet, after eighteen months of wondering how life would go on without her, life is going on. Without her. Just fine.

I’ve been consumed with the idea of an ethical break-up. What does it mean to split “amicably,” and how do you break up well? How do you weigh somebody’s feelings against what you know is the right thing to do? This feels like using reason to solve an emotional issue, which is not always helpful.

Here’s the jig: We all want to cut loose and run, but we don’t want to leave a heart broken in the dust behind our feet. This question of an “ethical break-up” is somewhat paradoxical. It’s like having an “ethical war.” Sure, you can agree not to target innocent civilians, hospitals, schools, and aid centers, but either way, people are getting killed!

D.S. Stollencraft hypothesizes that “human beings love to suffer” as long as there is an imagined “reward” for all of the pain. That may be why my guilt is eating me up so much. I don’t see a benefit to it, so then my suffering is just suffering for suffering’s sake. I’m not gonna write a great breakup album, movie, or play because I’m feeling really happy to have regained my agency as a single person. Which feels awful.

Artsy people tend to fetishize their own sadnesses so that, when atonement season comes around again, we can wallow in our own puddle of angst until our fingers prune. But what is God’s goal in Yom Kippur?

As it is written, “On the tenth day of the seventh month you shall afflict yourselves” (Leviticus 23:27). “Afflict” is the key word here, meaning to experience a struggle or hardship. Now I can only speak for myself, but with my acid reflux, actually eating food is more painful than going without it (if my punishment were to be tailored to me, then eating a really acidic tomato sauce would be the most painful way to get me to atone).

We are also quick to forget that fasting applies to other things than just food and water. The scriptures lay out the “five pleasures” that we should abstain from. These include sex, applying lotion, bathing, and wearing leather. Now, I don’t know about you, but I’m willing to bet a solid percentage of those in occupancy at the Temple Israel of Hollywood “Kol Nidre” service engaged in all four of those pleasures directly before driving their electric cars to Temple. All of this is to say that we are all hypocrites, and we follow the rules we think will benefit us most.

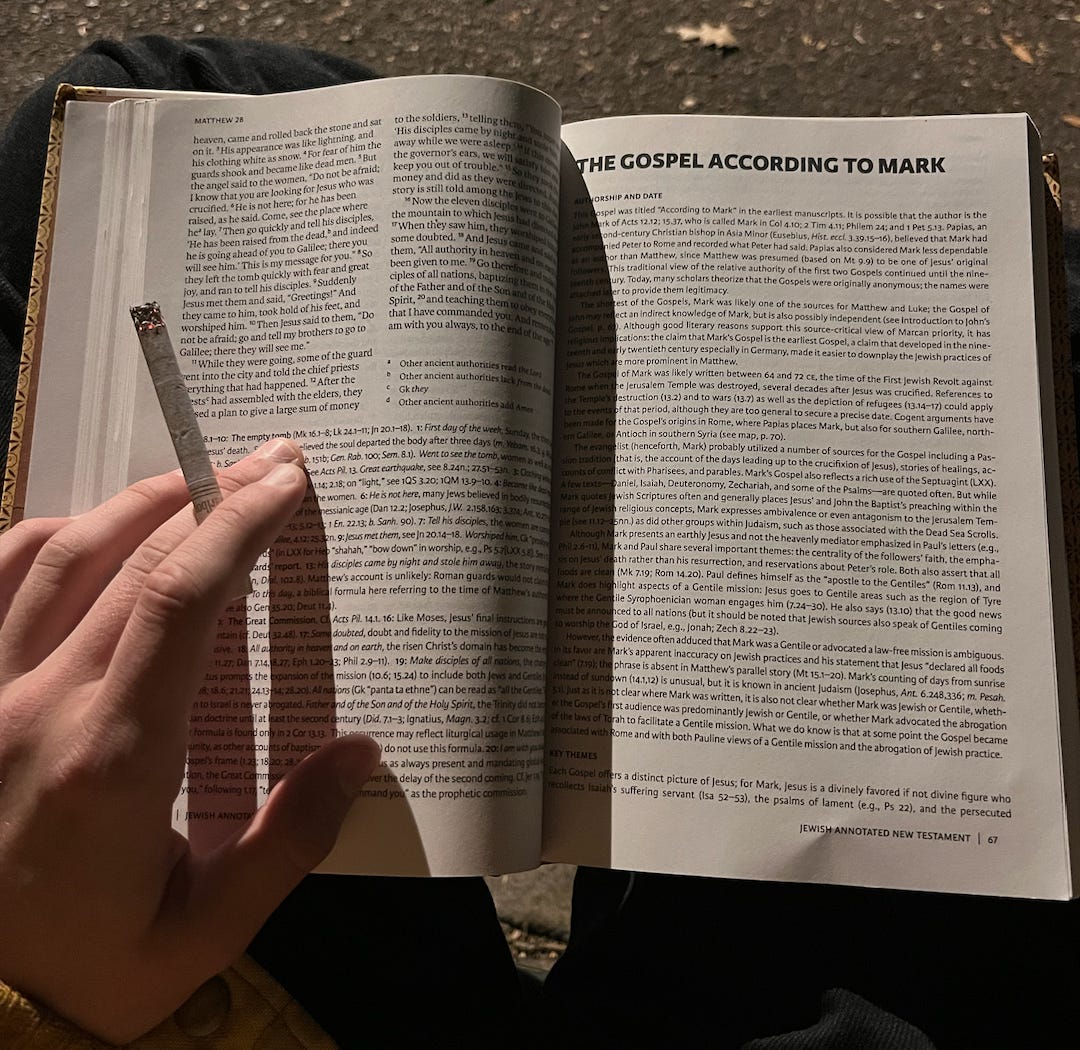

Last night, blind with hunger, I devoured the last five raspberries in my fridge, thus breaking my fast twenty-three hours early. Look, Fruit in New York is expensive, and it molds fast, and I figured it was “now or never.”

Immediately after eating the Raspberries, I collapsed on the couch, overcome with guilt over last month’s break-up. This was surprising because I am not a religious person, nor do I go to Temple, nor do I feel particularly connected with my Judaism. At that moment, it struck me that perhaps the religious guilt runs deeper than I thought. Perhaps feeling perpetually guilty is more “nature” than “nurture.”

I felt guilty for not fasting, which made me think “boy, I outta fast,” but then I felt bad because I had already failed so miserably at something I hadn’t even tried wholeheartedly to do. I also felt bad because I was drinking water. I cannot go twenty minutes without water.

…

Perhaps we fast because it’s easier than confronting our shortcomings day in and day out. If we can compartmentalize all of our imperfections to Yom Kippur, then the other 364 days become a whole lot easier. We ask God for forgiveness because we know we will get it, but we so often fail to make amends with those in our lives.

How many Jews atoned for their complacency in the Genocide in Gaza, or was that sin forgiven in advance by the Jewish God with a thirst for blood and destruction?

It feels wrong to suffer at your own hand when so many are suffering at the hand of another. To choose not to eat is a privilege so many do not have, and in a backwards way, Yom Kippur feels like God’s chosen people patting themselves on the back.

There are many productive things to do with your guilt: donate to charity, volunteer for the poor, write a book, create art, etc. With so many productive places to put your guilt, why give it to God – he’s not gonna do anything with it.

Confession: I hit the drive-thru McD after temple last night.

This is very very good.